I used to think I was good at staying focused. Then, I started writing historical fiction.

It began, as these things often do, with a single image. A girl in a forest, clutching something powerful and strange. A sense of time and place—muddy boots, wooden walls, a silence filled with birdsong and tension. I knew it wasn’t modern. I knew it was old. Anglo-Saxon, I suspected—but vague. I didn’t yet have names, or plot, or a clear timeline. What I did have was curiosity. And in historical fiction, that’s the most dangerous thing of all.

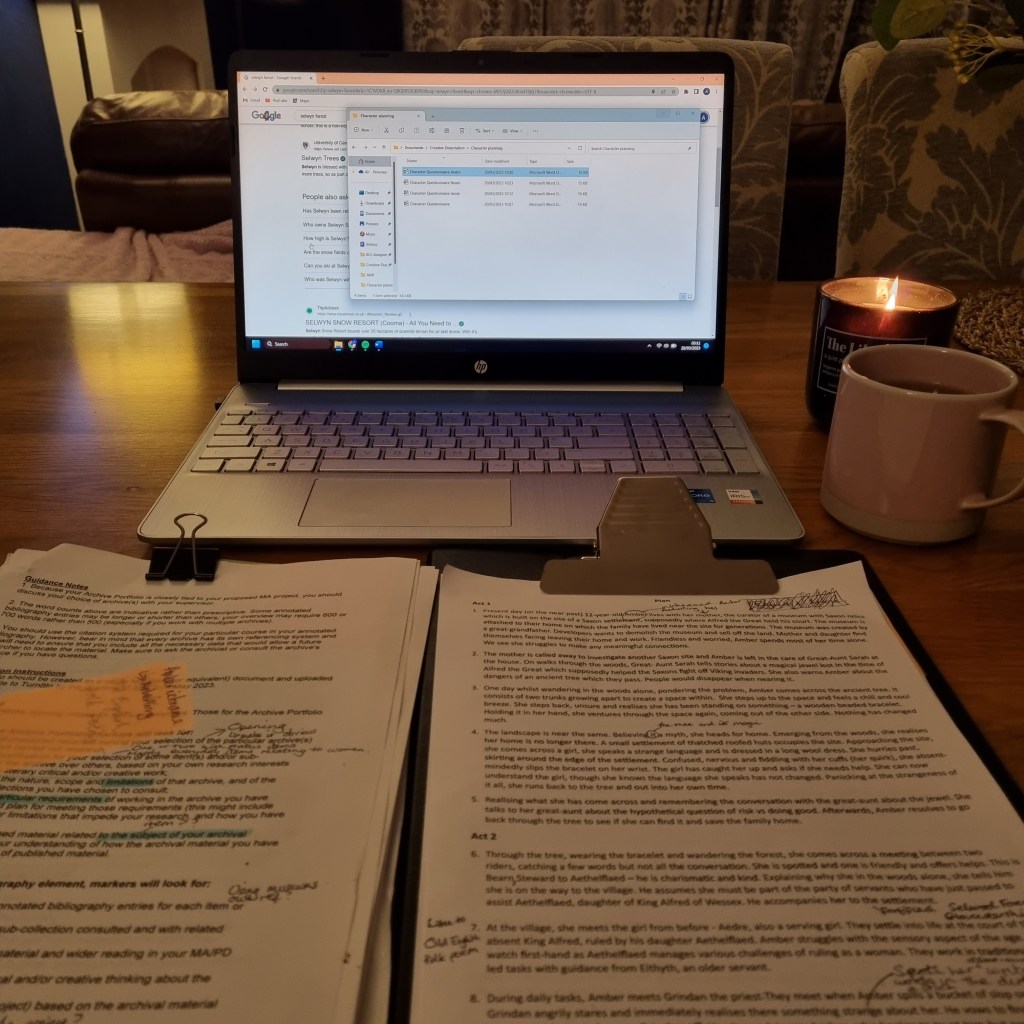

Curiosity means research. And research, I’ve discovered, is never just research. It’s a wild, addictive journey through other people’s lives. It’s the satisfying clunk of a puzzle piece fitting into place—and the frustration of realising there are a thousand more missing. It’s slow, strange magic. And it will steal your time, your tabs, and your sanity if you let it.

The 10% Rule (aka: Most of What I Learn Never Makes the Page)

When I first began The Jewel of Saxon Wood, I thought the hard part would be writing the actual story. But what surprised me most was how much of my time—hours, then days, then weeks—was spent researching things that barely showed up on the page.

At one point, I spent the best part of a weekend digging into Anglo-Saxon legal customs. Not because my characters were about to be arrested (though maybe they should’ve been), but because I wanted to write a single conversation between two elders discussing justice. In the end, one line from that entire rabbit hole made it in: something about a blood price and a broken oath. The rest? Cut. But still, it helped. Because even if the reader doesn’t see all the layers, they can sense when the world is built on solid ground.

That’s what research does—it builds the unseen foundation. It’s the scaffolding holding the story in place, even if no one ever notices it.

Falling Down the Rabbit Hole

There’s a certain madness to the way a historical fiction writer conducts research. We don’t start with a reading list and tick it off sensibly. Oh no. We start by looking up “Anglo-Saxon hairstyles” and end up reading about Viking funeral rituals, 11th-century weather patterns, or how to build a functioning lyre out of animal sinew.

One of my personal favourite tangents was herbal medicine. I’d originally planned a throwaway scene where a character wraps another’s injured hand. But what did people use back then? Turns out, honey and cobwebs were common—both antibacterial and readily available. The image of someone layering torn cloth with sticky honey and dusting it with webs was too vivid to pass up. Suddenly, that scene wasn’t throwaway at all—it revealed character, setting, skill.

Another time, I wanted to know what a child might carry in a small pouch. I assumed maybe coins or stones, but further reading unearthed items like carved amulets, charms against sickness, and even tiny bones from birds—symbols of protection or superstition. That one line became a symbol in the story, passed from hand to hand.

Balancing Fact and Fiction

This is the part I agonise over the most. I love history, deeply. I feel a responsibility to be faithful to the people who lived it. But I’m also writing fiction—and sometimes, the story needs to breathe.

For example, we don’t know exactly how long it took to travel between two burhs in winter. We have some idea, based on archaeological remains and logic, but no GPS logs from 873 AD. So I had to guess. Educated guesswork is a huge part of the job—balancing what’s known, what’s plausible, and what serves the narrative best.

Sometimes, I do bend history. Compress a timeline. Combine two minor historical figures into one character. Or imagine how a child might speak, even though no Anglo-Saxon child’s voice survives on record. But I do it carefully, and always with intent.

For me, the golden rule is this: the emotional truth must be honest. If the characters’ struggles, relationships, and decisions ring true to the time—even when built on fictional events—then the reader will believe it. And more importantly, feel it.

My Research Toolkit

If you’re curious (or secretly planning your own plunge into the past), here are a few tools and tricks I’ve leaned on heavily while researching:

- The British Library’s Digital Manuscripts Archive: You can zoom in on marginalia and even spot the finger smudges of long-dead scribes.

- Michael Wood’s documentaries and books: Insightful, vivid, and so readable. His work on Æthelflæd in particular was a gateway drug for me.

- The PASE Database (Prosopography of Anglo-Saxon England): A rabbit hole of names, dates, and locations. Great for naming characters without accidentally using a Norman name in 871.

- Local museums: Especially the small ones. They often have incredible knowledge hidden in obscure pamphlets and placards.

- Walking the land: I visited old hill forts, walked ancient pathways, and tried to imagine the world stripped of roads and buildings. Cold toes, but helpful.

Also: maps. I printed out maps of Anglo-Saxon kingdoms and scribbled all over them like a nerdy general preparing for battle. 10/10 recommend.

What It Taught Me

Writing historical fiction has changed how I write—and how I read. It’s taught me patience. Precision. A love for detail, and a respect for silence. It’s made me realise how little we really know, and how much room that gives for imagination.

I’ve learned to let research guide me without controlling me. To stop looking for the “right” answer when the sources disagree. And to trust that sometimes, the gaps in history are invitations, not barriers.

It’s also taught me how slippery our assumptions can be. That women weren’t always silent, children weren’t always powerless, and people in the past weren’t that different from us at all. They just had fewer options, more mud, and possibly worse shoes.

Over to You

So, now I’m curious—have you ever fallen down a historical research rabbit hole? Or found yourself unexpectedly fascinated by some forgotten fact? What’s your weirdest or most wonderful niche knowledge?

Drop it in the comments—I promise no judgment. Especially not if it involves medieval cheese.